Spoiler Alert

Data availability statement

Summarizing statement

Visualizing Deep Neural Networks in Virtual Reality

Abstract

In this paper, we improve upon existing Virtual Reality (VR) research with regard to the pedagogical use of VR for explaining Deep Neural Networks. We achieved a comprehensive understanding in five steps: a review of previous work in the field, a thorough characterization of existing issues, the development and programming of a novel VR-based software tailored for various ANN models, a detailed evaluation of this system, and a critical discussion on the future outlook and significance of this research. The results demonstrate the VR system's effectiveness in making complex AI systems more accessible to non-experts, thereby contributing to the field of explainable AI (XAI).

Keywords of the paper: ANN, XAI, Virtual, Reality, Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning

1. Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), accessibility remains a significant challenge, especially for those without a technical background. The European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), introduced in 2016, mandates the “Right to Explanation” for citizens impacted by algorithmic decisions (Xu et al., 2019). As AI systems grow more intricate, the demand for explainable AI (XAI) intensifies, as especially deep neural networks are often considered a black box (Minh et al., 2022). Integral to achieving XAI is the role of education. By educating students and professionals from diverse backgrounds in AI principles, ethical considerations, and the technology's potential impact, we can foster a generation better equipped to develop, manage, and understand AI systems.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), inspired by the biological neural networks in the human brain, have become a core technology in the domain of ML and AI. ANNs mimic the basic input-processing-output mechanism of a biological neuron, with the weights acting as a way to prioritize the importance of different inputs and the activation function serving as an analogy to the biological neuron's firing threshold (Basheer & Hajmeer, 2000). The interconnectivity in neural networks is mirrored in ANNs, allowing for computations in a highly parallel manner and enabling them to efficiently handle complex, multidimensional tasks (Jain et al., 1996).

Simultaneously, Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a revolutionary human-computer interface that strives to replicate a realistic environment, enabling users to immerse themselves in a virtual world (Zheng et al., 1998). Research showed that incorporating VR in classrooms introduces immersive simulation and active learning (Wang et al., 2018), boosting students' motivation and understanding of complex concepts through virtual manipulation of abstract ideas. As VR has demonstrated its visualization capabilities, it has emerged as a promising tool for advancing XAI (Jensen & Konradsen, 2018). By offering a VR-based system for visualizing ANNs, this paper aims to facilitate the exploration of abstract concepts of deep learning and enable non-experts to interact with a virtual representation of the ANN.

Therefore, the core contributions of this paper are 1) a systematic literature review of existing visualization approaches to this challenge; 2) the development of a set of algorithms that scale and display various ANNs for a VR use-case; 3) a VR application that integrates those algorithms; 4) a technical and descriptive evaluation of this tool.

2. Background

Beyond its established role in entertainment and gaming, VR is gaining momentum as an influential medium in educational contexts. The debate surrounding VR’s potential to revolutionize education is ongoing, with many experts believing it has the power to transform the way students learn (Ardiny & Khanmirza, 2018). The concept of immersion is particularly relevant in educational VR, as it can enhance concentration and give students a sense of presence in their learning environment (Jensen & Konradsen, 2018). Freina & Ott (2015) define immersion as "a perception of being physically present in a non-physical world by surrounding the user of the VR system created with images, sound, or other stimuli" (Freina & Ott, 2018, p. 1). Research showed that immersive VR simulations are more engaging and are taken more seriously by participants (Reiners et al., 2014), ultimately leading to improved learning outcomes. Head-mounted displays, which allow users to experience a high degree of immersion, have been widely adopted in educational VR applications (Jensen & Konradsen, 2018). This high degree of immersion increases a user's involvement in a virtual environment, which leads to their awareness of time and the real world becoming disconnected, providing a strong sense of "being" in the task environment. However, it’s important to note that in this context VR is a medium for learning and its effectiveness also depends on the quality of content and interactivity within the virtual environment (Jensen & Konradsen, 2018). Meanwhile, the use of VR in the flipped classroom context brings "immersive simulation, multi-user interaction, and real-time active learning" (Wang et al., 2018, p. 10), into the educational landscape. It enhances students’ motivation and understanding of complex concepts, enabling them to manipulate objects virtually and experience abstract ideas more concretely. Its application in architectural education allows students to perceive different architectural spaces through 3D objects and improves students' knowledge acquisition through interactive activities (Wang et al., 2018). Also, in the healthcare sector, VR is employed to facilitate the training of medical professionals before an operation or to explain medical options to patients (LaValle, 2023). The prominence of VR in these contexts is largely attributed to its ability to replicate real environments, which might otherwise be too expensive or pose significant health risks (LaValle, 2023). These examples illustrate that VR-based applications are particularly effective in making complex topics more accessible to a wide range of users. In the following chapter, we will detail our research and development approach to achieve this goal.

3. Research Approach

For the development of the artifact, this paper largely built upon the Design Science Research (DSR) approach defined by Peffers et al. (2007), as previous research has already shown its effectiveness in enabling meaningful VR-research (Vogel et al., 2021). DSR is a research methodology in information systems and computer science, primarily focusing on the creation and evaluation of artifacts, and is fundamentally grounded in the identification of real-world issues (Peffers et al. 2007). We also followed the guidelines outlined by Hevner et al. (2004), who puts a distinct focus on the "problem relevance" of the conducted research, meaning that a DSR study should focus on developing solutions to important challenges and problems. To achieve this, we conducted a literature review and systematically extracted issues from the existing literature to gain a larger understanding of the current state of research and identify common gaps, from which meta-requirements (MRs) were formulated as high-level objectives bridging problem and solution spaces, followed by establishing design principles (DPs) to guide the creation of an effective software artifact (Gregor et al., 2020). For this review, this paper followed the guidelines outlined by vom Brocke et al. (2009). First, we defined the scope of the review as all papers that use VR to visualize ANNs, which were published from 2017 to 2023. To achieve this, the search string (("VR" OR "virtual reality" OR "virtual world") OR ("issue" OR "challenge")) AND ("artificial neural network" OR "ANN") AND ("visualization" OR "visualizing") was used. Using this search string, we gathered the results from Google Scholar, SCOPUS, and Research Gate. Next, we filtered the results based on our scope defined in step 1. As the final step, the resulting papers were used to define requirements and guidelines for the development of the tool. We restricted the literature search to title, abstract, keywords as well as to publications in English and German. We identified 15 contributions after filtering the literature based on the abstract and keywords and remained with five relevant papers to inform the development of software artifacts in the context of VR and XAI.

The artifact, the VR application, is then evaluated based on these DPs in three iterations, in accordance with Peffers et al. (2007). We first defined and implemented the required algorithms. Afterwards, we integrated and evaluated them in a VR environment, using Unity and Meta Quest 2. Lastly, we developed and tested various User Interface (UI) elements that improve the quality and usefulness of users' interactions with the VR tool. We continually reviewed the intermediate prototypes, in accordance with Cockburn and Highsmith (2001), until the outlined MRs were met.

4. Artifact Description

4.1 Issues, Meta-Requirements and Design Principles

Based on the previously identified literature, we moved on to identifying key issues, meta-requirements, and design principles for our software artifact, in accordance with Gregor et al. (2020). In DSR, issues define real-world problems, leading to meta-requirements that specify essential conditions for solving them. Design principles then build on these meta-requirements, offering guidelines for developing effective solutions.

The first issue (I1) extracted from the reviewed literature of Meissler et al. (2019) highlights a limitation in current VR visualization approaches for neural networks, namely, the restriction to a single, static CNN model. This limitation hinders the user's ability to compare and understand differences between various neural network models. To address this, a crucial meta-requirement (MR1) calls for the dynamic modeling of multiple networks, enabling users to choose and seamlessly switch between different model architectures.

The second issue (I2) is the fixed user positioning in the VR environment, limiting interaction. To overcome this, a meta-requirement (MR2) suggests extensive spatial interaction, including free movement and locomotion control. The first design principle (DP1) emerges from these meta-requirements, advocating for a VR system that supports user-selectable models and enhanced spatial interaction, including free movement and teleportation. This integrated approach facilitates exploration, comparison, and a more immersive interaction with neural network models, significantly enhancing user experience.

Another issue (I3) identified in the prototype by Lyu et al. (2021) is the insufficient detail about the model and its parameters in the VR visualization, impacting its educational and explanatory value. The meta-requirement we derived (MR3) calls for more comprehensive information about the model, layers, and parameters to improve educational outcomes and model explainability.

Another issue in the work of Lyu et al. (2021) (I4) highlights the use of a simplistic neural network model, failing to showcase the variety and complexity of neural network architectures. From this issue, the resulting meta-requirement (MR4) demands support for more complex neural networks to leverage the VR space fully for detailed representation. This design principle (DP2) is derived from the meta-requirements (MR4, MR3) and aims to improve the visualization system by offering detailed insights into complex neural networks, including information about the model’s architecture, layers, and parameters, while enabling the representation of a broader range of neural network architectures. This principle aims to improve user experience and understanding of the ANNs by offering a detailed and expansive view of neural network models within the VR environment.

Another important issue (I5) in current VR visualizations of neural networks is the lack of dynamic scalability, particularly for different types of models. Previous works like those of Meissler et al. (2019) and Queck et al. (2022) primarily focused on single-model visualizations with static scaling approaches, failing to address the dynamic nature required for various models. Moreover, when the responsibility of scaling is placed on the user, as seen in approaches by Lyu et al. (2021) and Linse et al. (2022), it leads to two main problems: the representations of layers may not accurately reflect their true scale and complexity and that existing literature does not offer a standardized approach to scaling. This user-centric method can result in inconsistencies and inaccuracies in the visualization, making it challenging for users to gain a representative understanding of different layers and models. Therefore, a crucial meta-requirement (MR5) for the visualization is the development of an approach that ensures dynamic and automated scalability. This system should be capable of intuitively adjusting both the overall model size and individual layers’ scale, catering to different neural network architectures, without relying heavily on user input for scaling adjustments. In line with this requirement, the proposed design principle (DP3) is to develop a visualization system that dynamically adjusts layer sizes based on each layer’s output shape and automatically resizes the entire model to effectively display models of varying sizes and complexities. This principle also involves creating a generalized approach to scaling that reduces user intervention, ensuring that the visual representations of the layers and the overall model are both accurate and consistent.

The prototype by Linse et al. (2022) highlights the issue (I6) of visualizing the complexity and variability of neural network models, especially when displaying multiple models simultaneously. This complexity, due to the intricate interconnections and diverse functionalities of these models, can overwhelm users. The meta-requirement (MR6) is to balance complex network displays with user comprehension, by abstracting ANN network complexity without losing essence. Simplifications should make layers intuitive yet detailed as needed. The design principle (DP4) is to simplify neural network layer visualization, perhaps by grouping neurons or visualizing functionalities collectively, reducing cognitive load, and presenting layers as units with clear functions. This approach, while seemingly contradicting the principle of complex visualizations, actually complements it by enhancing user experience without information overload, focusing on how complexity is presented and navigated.

In Queck et al. (2022), an issue (I7) with users experiencing a sense of crowding in the VR visualization environment was identified. To address this, a meta-requirement (MR7) suggests a multi-faceted approach: optimizing the use of VR space by centrally positioning the model with room for exploration, providing information on-demand, and creating a dedicated UI interaction panel for general information and model switching. The design principle (DP5) derived from this is spatial optimization and user-controlled information, aiming to alleviate crowding by allowing exploration from all angles and ensuring information is accessible as needed. This principle enhances user experience by promoting comfort, engagement, and a customizable exploration pace, facilitated by a dedicated UI panel for easier navigation and understanding.

Compatibility issues (I8) between TensorFlow and Unity, especially highlighted by the performance constraints inherent in Unity’s ML-Agents Toolkit, were noted by Meissler et al. (2019). The primary issue lies in the direct integration of a deep learning framework within Unity applications, which can lead to significant performance bottlenecks, especially in resource-constrained environments like VR headsets. To address this issue, we derived the meta-requirement (MR8) to offload the model to a separate device to mitigate any performance issues on the VR headset itself. From this MR, a client-server architecture emerges as the optimal solution (DP6). This DP not only ensures the reliable compatibility between a deep learning framework and Unity for smooth model access but also manages computational loads by offloading the intensive model processing to the server. Such an architecture enables scalability and performance optimization, crucial for complex machine-learning models. Additionally, centralizing the ANN model management on the server simplifies the workflow, as it negates the need for uploading each model separately to the VR device.

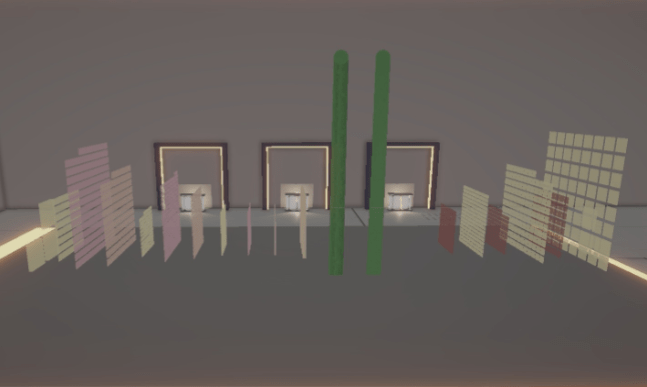

Figure 1. A visualization of an Autoencoder

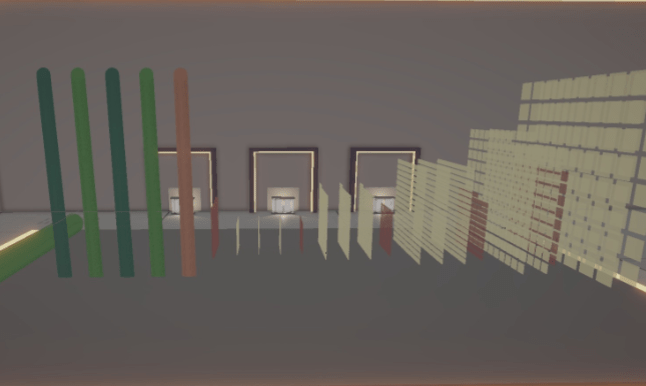

Figure 2. A visualization of a VGG model

Figure 3. The main menu to navigate the application

Figure 4. A separate menu for additional information

4.2 Application

In this section, we discuss the application of the established design principles utilizing Unity and the Meta Quest 2 headset for VR development. The integration and visualization of neural network models in a VR environment is achieved through a structured process that involves the retrieval, instantiation and visualization of layer information. The initial step launches by fetching layer data from a customized REST API. This integration is essential for overcoming the compatibility issues between TensorFlow and Unity using a server-based architecture (DP6). The VR application offers dynamic visualization capabilities for three distinct types of neural network model: a Sequential model, an Autoencoder (Figure 1) and a VGG (Visual Geometry Group) model (Figure 2). Adhering to the design principle of dynamic modelling of multiple networks, this functionality allows for user-selectable models (DP1), facilitating comparative analysis and exploration, and enabling users to understand the characteristics of different network architectures. The implementation also directly addresses the design principle of more complex network representation (DP2) by supporting more intricate neural network architectures. The UI in this project is structured to facilitate user interaction and provide educational insights into neural networks. The main UI (Figure 3) serves as the primary interactive hub for users and introduces the application. The educational aspect of the UI is divided into three distinct areas, each addressing a separate topic related to neural networks and their components (Figure 4). This approach aligns with the principles of providing comprehensive model information and the structured flow of the UIs aims to reduce cognitive load by presenting information in a manageable, step-by-step manner (DP4, DP5). Additionally, layer interaction within the network is made possible through the implementation of the XRSimple Interactable and an attached interaction script, offering in-depth information when the user actively seeks it.

4.2.1 Scaling and Positioning

Initially, each layer is instantiated with a default size appropriate to its type. This initial sizing provides a baseline from which further adjustments are made. The primary objective of these adjustments is to scale each layer to fit effectively within the context of the visualization. This process ensures that each layer is represented in a way that is visually coherent and contextually relevant. The core of the scaling approach is implemented in the ApplySelectiveScaling method. This method is designed to apply selective scaling specifically to convolutional layers. For each convolutional layer, the method calculates the layer's size using the CalculateLayerSize function. This function determines the size by aggregating the bounds of all renderers within a layer, providing a comprehensive size metric that encompasses the entire layer. The size is primarily measured along the x-axis, representing the layer's width in the virtual space. Once the size is calculated, a scaling factor is derived using the SigmoidScale function. The SigmoidScale function uses an adapted sigmoid function to achieve a smooth and controlled scaling of layers:

[ text{scaleValue} = text{scaleLimit} - left( frac{text{scaleLimit}}{1 + e^{-a(text{normalizedX} - 0.5)}} right) tag{1} ]

- scaleValue represents the resulting scaling factor calculated by the equation, indicating the degree to which a layer is scaled up based on the input parameters.

- a is the steepness parameter of the sigmoid function. It controls how quickly the output value of the function transitions from its minimum to its maximum value. A higher a value results in a steeper transition.

- scaleLimit represents the upper limit of the scale factor. It's the maximum value that the scaling factor can reach, effectively capping the degree to which a layer can be scaled up.

- normalizedX is the normalized form of the input value x. In the function, it's calculated as x / 9.0. Normalization is used to adjust the input value into a range suitable for processing by the sigmoid function.

The sigmoid function within the equation always yields a value between 0 and 1. Multiplying the scaleLimit by this value effectively reduces the maximum allowable size of the layer. If the exponent of e is higher, resulting in a larger value (e.g., 0.9), the reduction in scaleLimit is more significant. Ultimately, the scaleLimit is subtracted from the shrunken scaleLimit, yielding the new scale value. When the exponent of e reaches a certain value, the sigmoid function approaches 1, resulting in scaleLimit being subtracted from itself, effectively reducing the scale value to 0. This process ensures smooth and controlled scaling of layers within the visualization context, where outliers, such as exceptionally large or small layers do not take an overbearing part of or disappear completely in the VR visualization of the same network.

To manage the model's overall depth, the PositionLayers function arranges all layers and applies necessary scaling adjustments to fit within pre-defined spatial limitations. It begins by setting a starting z-position and defines a maximum allowable depth. The crucial step in this process involves calculating a uniform scaling factor for the entire model using the CalculateScaleFactor function:

[ f(text{annDepth}, text{maxDepth}) = begin{cases} dfrac{text{maxDepth}}{text{annDepth}}, & text{if } text{annDepth} > text{maxDepth} 1, & text{otherwise} end{cases} tag{2} ]This function determines whether the total depth of the ANN exceeds the maximum permissible depth. If it does, the function computes a scaling factor to proportionally reduce the size of the entire model. The function calculates the scaling factor by dividing the maximum depth by the actual depth of the ANN. This results in a factor of less than 1, effectively reducing the size of the entire model proportionally. Those scaling and positioning methods effectively fulfil the established design principle of dynamic scalability (DP3).

5. Evaluation

The evaluation covers a technical/descriptive analysis, assessing visualization and information representation of the networks and examining the realization of design principles during the iterative development steps of our project, as outlined by Peffers et al. (2007). The first iteration was guided by DP5 and DP6. We successfully achieved the visualization of a single model, which is a simple sequential model with a basic architecture composed of 8 layers. In the second iteration step, focused on individual layer information and educational content, we tackled the lack of detailed model information by applying design principles two and four. The realization involved providing comprehensive information about the models and their components and the strategic structuring of UIs. To address the sensation of crowding and realizing DP7, we focused on spatial optimization and user-controlled information access. This was realized through strategic structuring of the VR environment, ensuring clear and accessible information with designated areas for UI interaction and detailed layer information. The third iteration step, guided by DP1 and DP3, primarily focused on dynamic models with a larger variety in layers. We successfully adapted the previously static model display to a much more flexible software that can display all non-recurrent models, independent of the number of layers. In this context, the proposed scaling function proved especially valuable when it comes to displaying different models with various numbers of layers in a usable way.

During the iteration steps, we encountered various challenges, like efficiently visualizing individual neurons within each neural network layer. Initially, instantiating each neuron with its prefab proved computationally demanding, particularly for layers with numerous neurons. This raised concerns about computational efficiency and user experience. To address this, we chose to represent neurons within a layer as a cohesive unit rather than individually. Implementing a dynamic particle system burst scaled neurons based on layer size, striking a balance between visual clarity and efficiency. Secondly, the exploration of the Autoencoder model revealed significant performance challenges due to its large scale and numerous parameters. Despite optimization efforts, including light baking, static batching, and single pass instancing, performance problems persisted. Future solutions might involve upgrading to a more advanced Meta Quest headset model, known for improved performance, to enhance user interaction (Brecher, 2023). The compatibility challenge between TensorFlow and Unity was addressed early on by moving to a server-client architecture, in which the AI model was deployed on the server and the information about the model was retrieved by the VR client via a REST API (Masse, 2011). This effectively solved the compatibility challenge between TensorFlow and Unity. Addressing network connection failures in the VR headset during Unity web request operations presented another significant challenge, leading to automatic internet access disabling. Despite attempts to resolve this through plugin downgrades and manifest modifications, the issue persisted until manually updating to Open XR version 1.9.1 and disabling the option to force remove internet access, ultimately stabilizing the network connection.

6. Discussion and Future Research

Compared to previous approaches, our software artifact addresses numerous issues. Mainly, the realization of the Design Principles concerning the flexibility and scalability of the developed artifact achieved a significant broadening of potential VR utilization in the context of XAI, by adding the ability to look at and get detailed information for various models. Especially the two scaling functions outlined in chapter 5.2.1 enabled the display of wide range of models, starting with very small classifiers for datasets like MNIST, as well as for very large ANN architectures, like the ResNET.

An important limitation of this paper is the lack of a quantitative user-based evaluation, to really show the advantages of using the VR tool compared to more traditional teaching formats when it comes to explaining how modern deep neural networks work. Another limitation to the scope of this work is that technical aspects of XAI with regard to the precise decision-making processes within ANNs are not part of this work, for example, when it comes to methods of explaining the internal processes of ANNs as introduced by Montavon et al. (2018). Consequently, while users may grasp a better understanding of the overall structure of modern ANNs through our work, they may still lack insight into the detailed inner workings of ANNs.

Furthermore, to achieve its full potential, this paper also identified numerous extensions to the artifact, that may be addressed in future research. From an educational perspective, one of the main issues that are left to be addressed is that the artifact is still developed for a single user, while studies have shown repeatedly, that collaborative learning leads to significantly better outcomes (Laal & Ghodsi, 2012). This issue also persists from a teaching perspective, as a collaborative environment would significantly enhance the time efficiency of the tool by enabling the teacher to guide multiple students simultaneously through the VR environment.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper presents some significant advancements in the use of Virtual Reality (VR) for the pedagogical explanation of Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), contributing to the broader field of explainable AI (XAI). The developed VR software enhances the accessibility of complex deep neural networks for non-experts through its flexible and scalable design, effectively broadening the potential applications of VR in explaining various ANN models. This adaptability is crucial in accommodating a range of models from simple classifiers to complex architectures like ResNET, thus facilitating a more comprehensive educational tool.

However, the research highlights important limitations and opportunities for further development. Notably, it lacks a quantitative user-based evaluation to empirically validate the VR tool's advantages over traditional methods, and it does not delve into the intricate decision-making processes within ANNs. Future enhancements could include collaborative learning functionalities to allow for multi-user engagement, which could significantly improve educational outcomes by enabling teachers to guide multiple students simultaneously in the VR environment, thus extending the educational impact of the tool.

References

Ardiny, H., & Khanmirza, E. (2018). The role of AR and VR technologies in education developments: Opportu- nities and challenges. 2018 6th RSI International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (IcRoM), 482–487. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRoM.2018.8657615.

Basheer, I. A., & Hajmeer, M. (2000). Artificial neural networks: Fundamentals, computing, design, and application. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 43 (1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-7012(00)00201-3.

Brecher, H. (2023, September). Meta quest 3 startet für 549 euro mit doppelter performance und gaming-fokus [[Accessed 01-10-2024]]. https://www.notebookcheck.com/Meta-Quest-3-startet-fuer-549-Euro-mit-doppelter-Performance-und-Gaming-Fokus.756350.0.html.

Cockburn, A., & Highsmith, J. (2001). Agile software development, the people factor. Computer, 34 (11), 131–133.

Freina, L., & Ott, M. (2015). A literature review on immersive virtual reality in education: State of the art and perspectives. https://doi.org/10.12753/2066-026X-15-020.

Gregor, S., Chandra Kruse, L., & Seidel, S. (2020). The anatomy of a design principle. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 21, 1622–1652. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00649.

Hevner, A., R, A., March, S., T, S., Park, Park, J., Ram, & Sudha. (2004). Design science in information systems research. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 28, 75.

Jain, A. K., Mao, J., & Mohiuddin, K. M. (1996). Artificial neural networks: A tutorial. Computer, 29 (3), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1109/2.485891.

Jensen, L., & Konradsen, F. (2018). A review of the use of virtual reality head-mounted displays in education and training. Education and Information Technologies, 23, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9676-0.

Laal, M., & Ghodsi, S. M. (2012). Benefits of collaborative learning. Procedia-social and behavioral sciences, 31, 486–490.

LaValle, S. M. (2023). Virtual reality. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/virtual-reality/0EC0542C3688B5CA3E9733011DC8DEC2.

Linse, C., Alshazly, H., & Martinetz, T. (2022). A walk in the black-box. Neural Computing and Applications, 34, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-022-07608-4.

Lyu, Z., Li, J., & Wang, B. (2021). AIive: Interactive visualization and sonification of neural networks in virtual reality. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), 251–255. https://doi.org/10.1109/AIVR52153.2021.00057.

Masse, M. (2011). Rest api design rulebook: Designing consistent restful web service interfaces. ”O’Reilly Media, Inc.”.

Meissler, N., Wohlan, A., Hochgeschwender, N., & Schreiber, A. (2019). Using visualization of convolutional neural networks in virtual reality for machine learning newcomers. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), 152–1526. https://doi.org/10.1109/AIVR46125.2019.00031.

Minh, D., Wang, H. X., Li, Y. F., & Nguyen, T. N. (2022). Explainable artificial intelligence: A comprehensive review. Artificial Intelligence Review, 1–66.

Montavon, G., Samek, W., & Müller, K.-R. (2018). Methods for interpreting and understanding deep neural networks. Digital signal processing, 73, 1–15.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M., & Chatterjee, S. (2007). A design science research methodology for information systems research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24, 45–77.

Queck, D., Wohlan, A., & Schreiber, A. (2022). Neural network visualization in virtual reality: A use case analysis and implementation. In S. Yamamoto & H. Mori (Eds.), Human interface and the management of information: Visual and information design (pp. 384–397). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06424-12_8.

Reiners, T., Ter¨as, H., Chang, V., Wood, L., Gregory, S., Gibson, D., Petter, N., & Teräs, M. (2014). Authentic, immersive, and emotional experience in virtual learning environments: The fear of dying as an important learning experience in a simulation.

Vogel, J., Schuir, J., Koßmann, C., Thomas, O., Teuteberg, F., & Hamborg, K.-C. (2021). Let’s do design thinking virtually: Design and evaluation of a virtual reality application for collaborative prototyping.

vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Niehaves, B., Riemer, K., Plattfaut, R., & Cleven, A. (2009). Reconstructing the giant: On the importance of rigour in documenting the literature search process. 17th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), 161.

Wang, P., Wu, P., Wang, J., Chi, H.-L., & Wang, X. (2018). A critical review of the use of virtual reality in construction engineering education and training. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061204.

Xu, F., Uszkoreit, H., Du, Y., Fan, W., Zhao, D., & Zhu, J. (2019). Explainable AI: A brief survey on history, research areas, approaches and challenges. In J. Tang, M.-Y. Kan, D. Zhao, S. Li, & H. Zan (Eds.), Natural language processing and chinese computing (pp. 563–574). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32236-6 51.

Zheng, J., Chan, K., & Gibson, I. (1998). Virtual reality. Potentials, IEEE, 17, 20–23. https://doi.org/10.1109/45.666641.

Leonie Grafweg

Personal Motivation

As someone who is interested in human-centered AI, I’ve witnessed firsthand how family and friends constantly struggle to grasp its complexities. This observation fuels my motivation to make AI-related topics accessible to everyone. Immersed in the realms of AI and VR design, I was driven to create an experience that transcends abstract concepts and brings understanding to life. Picture stepping into a virtual world where neural networks unfold before your eyes, turning complexity into an interactive experience.

Cornelius Wolff

Personal Motivation

When it comes to exploring more complex setups of emergent behavior of AI in any kind of setup, one of the biggest problem that the scientific community is facing, is the problem of explainable AI. Especially to people not familiar with the topic, AI can often seem like magic. In this context, I find it particuallary interesting, how recent advances in VR/AR can be used to more effectively explain how modern AI models work.